Summary

The written word has so far been distributed in books and pages. The logic of a text in written or spoken form is linear and sequential and the meaning is determined by the word and paragraph order. An image on the other hand has a spatial logic where meaning is determined by the relation between different elements in the image. To this can be added other meaningful forms such as movement and voice. In today’s educational landscape, sound and image are made available in various forms via digital media and should be used to strengthen or test students’ understanding. We find out different things about students’ knowledge in different forms (modalities). Sound captures mood, identity markers, and commitment. Thought or concept maps show relationships and what these consist of (eg dependencies, consequences, derivations and results). Graphics capture and strengthen mathematical relationships, connections and sizes, and text captures the story, its nuances and meanings in its word choices. The screen has its own logic and we are increasingly making choices between different forms aware of their inherent meaning offerings.

The written word is thus no longer the bearer of complete meaning, if it ever was. Today, text is a player in a meaningful ensemble. It has consequences for how we illustrate, represent, shape and measure knowledge both in our learning act but also for the knowledge representations we demand of our students.

There is a risk that online education becomes static and asynchronous and stacks resources on top of each other for students to consume and thus lose the strength of other forms of meaning.

Video simulations and case studies

Video simulations are highly suitable for integrating several learning objectives and thereby tackling complex areas of knowledge, promoting interactivity and, if desired, offering a clear collaboration focus.

Emergency Services Exercise supported by Interactive Technologies: Trailer from Medieteknik Lnu on Vimeo.

A web-based interactive simulation enables students to choose their specific professional role / perspective in a video simulation and then follow the course of events from different perspectives such as 360 degrees, drones or recording from a body camera. The simulation integrates both active choices and reflective questions based on each profession. The questions can touch on key aspects such as teamwork, communication, safety, division of roles, different clinical practices and the importance of a common objective, but also generic skills that are often difficult to examine such as independence and critical thinking. 360 degree video technology can potentially increase the pedagogical benefit of use in nursing education compared to regular film as it increases the level of interaction when students can choose perspective (Donovan et al, 2018: Dubovi et al, 2018 and Herault et al: 2018 see below).

In a campus program, a student with good basic knowledge would undergo an applied exercise / practical simulation which then, with feedback / reflection, can lead to an increased mental preparation and expanded knowledge base. This is problematic from several aspects. Not least because it is very resource-intensive in the form of training environments, actors etc. Clinical / practical exercises can also in themselves cause stress in students, which can be negative for the learning process (Bong, Fraser, & Oriot, 2016; Pai, Ram, Madan, Soe, & Barua, 2014). However, it must be remembered that the pedagogical gain is not always in proportion to the resource consumption. Laurillard, 2013 (Chapter 10) believes that simulation with adaptive technology can potentially promote exploratory learning and based on active actions / choices contribute to internal feedback (Laurillard, 2013). Simulation in healthcare constitutes a context where elements of self-regulatory learning can contribute to learning (Abelsson, Rystedt, Suserud, & Lindwall, 2016; Brydges et al., 2015).

For further information on this please contact Martin Olsson, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences. martin.k.olsson@lnu.se.

Student generated films as active processing

The film as a representation has proven successful in professional education (such as teacher training programs) to get students to process challenging and theoretical course literature or to understand the importance of theoretical perspectives in complex areas of knowledge. In the form of digital storytelling, film production has also been used successfully to work with professional meetings in healthcare where films have been produced with so-called war stories in clinics (Petrucco, 2014) but also for blue-light staff.

Complex situations in professional practice that are not subject to routines but require creative and unusual solutions are well suited for digital stories,

All voices and perspectives on the situation are gathered in an initial very important phase which involves a negotiation of meaning and understanding of the situation around which knowledge is to be created. Listeners and participants will all be co-creators of the narrative that will be the starting point for the film / representation that will then be produced. The product can then be reused in undergraduate education if it has been developed, for example, by students in later phases of their education or professionals.

Teacher videos

Video is widely used in teaching today by both teachers and students. Most often it is in the form of recorded lectures or reviews. Before recording a tutorial, consider the following:

- Recorded lectures should be short and concise. Better to make short (max. 10 minutes) lectures rather than one long one. See suggestions on how a lecture should be set up under Independent and motivated students – Develop your lecture.

- If you are making a series of recordings, make sure that each film refers to the overall context and show how each film contributes to the whole.

- Create interactivity even in a recording! Ask the students a question, ask them to pause and write down their answers on paper, and then return to your recording. Alternatively, ask a reflection question at the end of the recording and ask them to write their answers in a forum or collaborative document that you can then provide feedback on. When you then meet in a synchronous meeting, the students are already quite familiar with the issues to be discussed.

- In LnuPlay (Kaltura) you can build questions into your recordings (yes / no, multiple choices, reflection). The student must answer the question before he can proceed in the film. Watch the movie How to Create a Video Quiz (English subtitles are available by pressing the CC button in the video window)

- If you want to be able to reuse the recording in other courses, you should make sure not to refer to seasons or current news. A film with Christmas decorations in the background has great limitations for recycling!

- Do not film casually. Think about purpose.

Audio recordings have several benefits for both teacher and student. Sometimes video is simply unnecessary, especially if it’s just a talking head in the box. Aa audio recording promotes the art of listening and you avoid disturbing images and movements. In addition, audio recordings are more accessible because they do not take up as much bandwidth as video. The student can listen to a podcast or voice message at any time on a mobile device and the files can be easily downloaded and are then accessible without an internet connection.

Typical applications:

- Create a teacher podcast to summarize each week’s activities in the course and highlight student achievement.

- Alternatively, a student podcast where students take turns summarizing the week’s course activities and important lessons etc.

- Record interviews or a discussion with external experts. Here the focus is on the spoken word, not slide shows and faces.

- Feedback on assignments with screen recording and voice. Go through the student’s essay, mark important sections and comment orally. Personal feedback without video.

- Discussion thread with voice comments. Record your question to the students as a voice message in a forum. Ask them to answer orally. The discussion immediately becomes more personal and takes on a different character than a written discussion thread.

Hybrid teaching means that you teach in a classroom with students both on site and online via, for example, Zoom. So you teach both on site and online. Hybrid teaching involves many challenges such as capturing both the teacher’s activities and the students’ activities in the room, which makes it a difficult form of teaching to arrange without more advanced technology and preparation or specially equipped premises. The conditions for communicating with the different groups differ and therefore you risk not responding to either group in a good way.

Traditional lecture teaching is relatively easy to organize in hybrid format with a camera and a good microphone for the teacher as well as screen sharing of slide shows in Zoom. The problem is that the distance students are often invisible to both teachers and students in the hall and there is a risk that the distance student feels like a fly on the wall, a mere spectator. The result is that questions and comments from the classroom are prioritized and the online students have difficulty getting their voices heard.

Consider the following:

- use a room with several screens so that the online students are clearly visible at all times and the teacher can address them directly.

- a control panel is needed where the teacher can control the cameras in the room (preferably two), slide shows, the gallery view of the distance students, etc.

- At best, have an assistant to handle a mixer.

- the room should also be equipped with several microphones so that student questions in the room can be heard by all.

Group work can be arranged in a hybrid solution by the distance students joining breakout groups in Zoom while the classroom students physically group themselves in the hall. Everyone should be able to take notes on a common workspace (Box, Google Docs, Padlet, Miro, etc.) so that all discussions are gathered in one place.

Alternatively, you can create groups with a mix of classroom and distance students in each group, but this solution requires that the classroom students have their own computers with headsets and can connect to Zoom and be part of breakout groups. It also requires that they spread out outside the classroom so as not to disturb each other.

Another concept is hyflex, which means that all course activities can be carried out synchronously in the classroom or at a distance, as well as asynchronously via recordings and assignments. Read more about the model in an article in Educause: 7 Things You Should Know About the HyFlex Course Model.

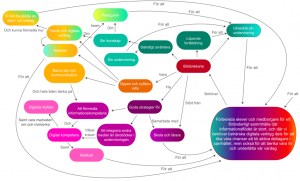

What is a mind map/concept map?

The maps are visual representations where knowledge emerges in the form of relationships, patterns, relevant content and ambiguities that follow a different logic than a linear text presentation. Mind maps are excellent to use in an exploratory phase and as a basis for a conversation / discussion / presentation but also as an examination.

Concept maps are useful as an examination task or in a more advanced assignment where students must represent their knowledge,. Then the mind map can capture an integrated network of concepts that demonstrate a basic structured understanding. Among other things, it can be traced to levels in the map, the number of concepts and the complexity of how they relate to each other. The various ”bubbles” in the map must therefore be linked in text so that you can follow how the links between them are made. They can be used as a basis for a seminar or oral examination or even as a recording where the student explains their map. The main point here is the work of producing the map that can be supervised so that it contains certain concepts or phenomena or based on a particular topic to illustrate what the students perceive and see.

See example below:

Donovan, L. M., Argenbright, C. A., Mullen, L. K., & Humbert, J. L. (2018). Computer-based simulation: Effective tool or hindrance for undergraduate nursing students? Nurse education today, 69, 122-127.

Dubovi, I. (2018). Designing for online computer-based clinical simulations: Evaluation of instructional approaches. Nurse education today, 69, 67-73.

Herault, R. C., Lincke, A., Milrad, M., Forsgärde, E.-S., & Elmqvist, C. (2018). Using 360-degrees interactive videos in patient trauma treatment education: design, development and evaluation aspects. Smart Learning Environments, 5(1), 26.

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014) How video production affects student engagement: an empirical study of MOOC videos. In Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning @ scale conference (L@S ’14). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 41–50. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/2556325.2566239

Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a Design Science: Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology. New York: Routledge.

Petrucco, C. (2014). Digital storytelling as a reflective practice tool in a community for professionals. Paper presented at the E-Learning at Work and the Workplace:From Education to Employment and Meaningful Work with ICTs, Zagreb.

Raes, A., Vanneste, P., Pieters, M., Windey, I., Van Den Noortgate, W.,Depaepe, F. (2020) Learning and instruction in the hybrid virtual classroom: An investigation of students’ engagement and the effect of quizzes. Computers and education Vol 143, Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103682.

Selander, S. (2017). Didaktiken efter Vygotskij: Design för lärande. Stockholm: Liber.

Selander, S., & Kress, G. (2017). Design för lärande: ett multimodalt perspektiv. (Andra upplagan). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Selander, S. (2016). Conceptualization of Multimodal and Distributed Designs for Learning. In B. Gros, Kinshuk, & M. Maina (Eds.), The Future of Ubiquitous Learning : learning Designs for Emerging Pedagogies (pp. 98-112). Berlin: Springer.